1000 Miles in 24 Hours - The Report

The Iron Butt Association is a group dedicated to Long Distance Motorcycling. It is easy to climb aboard a bike and ride it, even to ride it a long way, but to do so without preparation is to both invite disaster, and pain probably in equal measure. It is also fair to say that a long distance to most riders would be a short afternoon drive for the dedicated LD Riders. We might consider two to three hundred miles perched atop a motorcycle to be a longish distance, and it is; but the Iron Butt rides start at one thousand miles, and just get longer.

One thousand miles in less than twenty four hours, with every mile independently verifiable. That is the challenge, and it requires planning. As we will see later, it also require doing, and that it is possible to over-plan. Built in flexibility will pay dividends down the road.

Just under a year ago I paid $250 for a wreck of a motorcycle. It is a 1977 Yamaha XS750-2D.

The bike had been stored for years under a lean-to. The tyres were rotted out, some large bits were missing, and the years had seen it become less of a motorcycle, and more of a home to various species of Oklahoma wildlife. The aim was to get the bike running, mechanically safe and sound, and create a decent machine for Jodie and I to enjoy on weekends. It would be nice to improve the appearance a little, but Iím not a guy who enjoys polishing. I like to tinker, and I love to ride.

The re-build went fairly smoothly, and involved a modest outlay, lots of waiting for UPS, and some enjoyable spannering sessions. Slowly the bike took shape, and within a couple of months was back on the road. That was a nice time and we covered maybe 2500 miles last fall.

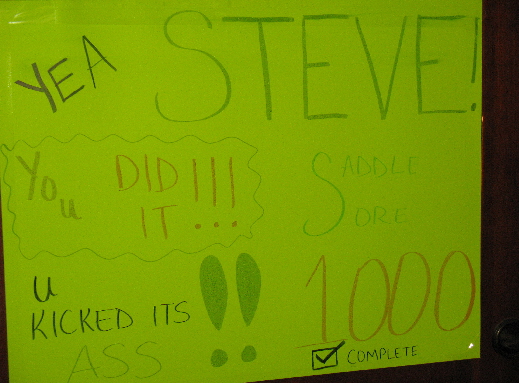

It wasnít enough. I had read about the Iron Butt Association, and it intrigued me. Even the introductory ride, the Saddle Sore 1000, is a prodigious riding feat, well justifying the label of The Worldís Toughest Riders. I am not tough. Iím just me, Steve, a middle-aged family man with no pretensions to toughness. Ask the kids, Iím a pushover.

Here was what caught my imagination. Could this bike that I basically rescued from a barn, carry me, husband, dad and regular guy, one thousand miles in less than twenty four hours? And could it do it safely, with at least a modicum of hope that we both might arrive back in one piece, and under our own steam?

Well we nearly didnít make it, but make it we did, and here is how¶.

The idea took hold in about September of last year (2010). We had ridden the bike a few times, and I had been wondering just how competent it was. ItĎs an old bike, 34 years old now, and does need quite a bit of babying, a bit like its rider, I guess. Never once though has it let us down while out riding, so what if the ride were to be a little longer than average? I had something to prove to myself, and so I set about planning to ride the Saddle Sore 1000. Any of the rides are possible, but this is the one that is fairest of all to ask of the motorcycle. No point pushing your luck.

I used mapping software to begin working out routes. A straight out one thousand miles is possible in pretty much any direction from here, but that puts you one thousand miles from home, so a circular route, or an out and back five hundred works best. I planned three routes, all starting from home in Owasso, OK. I could go straight out West to Tucumcari, NM, south to Austin, TX, or a circular route taking in Oklahoma City, Wichita, KS, Kansas City, on to just short of Indianapolis, and back home. In the end I decided west to New Mexico, because I wanted to see New Mexico, and I didnít want to negotiate the traffic in Dallas and Austin, and who the hell wants to drive across Kansas?

The mapping software allows for very detailed planning, so I did. I had my route, including all the stops loaded into the Garmin GPS, and was set, so I thought, for a routine trip. The bike was prepped by changing all the fluids and checking that everything was functioning well. I have a full Vetter fairing, with lowers, and a full pannier set on the back. The most used item was my tankbag. I bought two RAM mounts to carry the phone and GPS, and would highly recommend them. I have a Motocomm intercom, which worked in some ways, and didnít work in others.

I was carrying plenty of snacks and water, a decent toolkit, two gallons of gas and a quart of oil. The biggest concern was the weather. I had been following the forecast, and the overnight low for the night concerned was 45F. This after a 70+ day with 66F the high on the Sunday. 45F is chilly, that is for sure, but itís only for a few hours and is quite manageable with the clothing I had, including a good pair of winter motorcycling gloves. I had estimated the trip to take twenty hours and I wanted to arrive back in daylight. It seemed sensible to do the last bit of the journey, when you are tired, in daylight rather than in darkness, so I went for a start time of 10.00pm on Saturday 12th March.

I was carrying plenty of snacks and water, a decent toolkit, two gallons of gas and a quart of oil. The biggest concern was the weather. I had been following the forecast, and the overnight low for the night concerned was 45F. This after a 70+ day with 66F the high on the Sunday. 45F is chilly, that is for sure, but itís only for a few hours and is quite manageable with the clothing I had, including a good pair of winter motorcycling gloves. I had estimated the trip to take twenty hours and I wanted to arrive back in daylight. It seemed sensible to do the last bit of the journey, when you are tired, in daylight rather than in darkness, so I went for a start time of 10.00pm on Saturday 12th March.

Everything was organized and tested. Panniers on the bike had spare gas, tools and oil. Top case was carrying clothes, a couple of cushions and water bottles, and I was ready. I was mindful of the name of this organization, the Iron Butt, and had tried to prepare accordingly. I know what saddle sore feels like, but I wanted to minimize it. I had seen an ATV seat cover in Walmart, so I bought one and fitted it. There is the first lesson. Never try something new on a ride like this, just donít do it. I was thinking of writing to the makers of that seatcover and letting them know that, after four hundred miles in the saddle, their padded seat cover sucks! Previously I have rebuilt my seat, the stock seat being useless, and I have to say that while my amateur efforts are no substitute for a Russell Day Long, but they are tolerable.

The Kum & Go gas station is one mile from home, so I started there. Filled up with gas, recorded the mileage, started my countdown clock at 24 hours and kissed my wife goodbye. A friend who has completed two of these rides agreed to be my start witness, and he rolled up on his Vulcan a few minutes before I left. When I saw Bill there, on his bike I half hoped he had decided to come along for the ride. In my heart I knew that he respected my wish to do this on my own, but at that moment, with Jodie and Bill waving me off, I felt very alone, and I didnít want to go.

I pulled away and it was a short drive to Highway 169 South. Headed down there and onto I 44 West. I was going to see a lot of both I 44 and I 40, they were the bulk of the route. I made good time down the Turner Turnpike to Oklahoma City and during that phase I discovered that the intercom wasnít handling the phone well at all. I tried to call Jodie. I could hear her perfectly, but for some reason my microphone was useless. It worked just fine when I tested it a few days earlier, but had chosen a great time to fail.

When I hit OKC, I needed gas. I had a stop programmed into the Garmin, and that is where I learned the second lesson. By all means  ensure there is gas along your route, but donít over plan. I had covered about 110 miles, and spotted a handy place to stop, so I did. I filled up, entered the mileage, etc in the log, and fed the numbers into the program on my phone. That told me something useful for a change. The bike had run 36mpg, its best ever, and it gave me a great figure to work with. From here on I knew to start looking for gas as I approached 120 miles on the trip meter. One hundred and twenty miles is also about as much as I can stand in one stretch, so all was good.

ensure there is gas along your route, but donít over plan. I had covered about 110 miles, and spotted a handy place to stop, so I did. I filled up, entered the mileage, etc in the log, and fed the numbers into the program on my phone. That told me something useful for a change. The bike had run 36mpg, its best ever, and it gave me a great figure to work with. From here on I knew to start looking for gas as I approached 120 miles on the trip meter. One hundred and twenty miles is also about as much as I can stand in one stretch, so all was good.

Headed south from there, then West onto I 40. On the trip down to OKC the temperature had held steady at around 60F, and I called Jodie saying I was too warm in all the gear. I changed the winter gloves for my summer pair, and my hands appreciated that. Another one hundred or so miles found me in Canute, a small place just short of Elk City, OK. The gas station was modern, but closed. The pay at the pump was fine, so I filled up and called home. Life was good at this point, and I was beginning to entertain the hope that this was, in fact, do-able.

As I continued along the I 40 west, the temperature plummeted. This was not in the forecast. The forecast low was 44F, yet my fancy phone was telling me that the current temperature was 35F. I didnít need the phone to tell me it had suddenly dropped very cold. Thirty five degrees Fahrenheit, when you are rolling along at 70 mph on a motorcycle has a way of making itself known. My hands were hurting when I rolled into the Loves about ten miles short of Amarillo, TX. I didnít know it then, but this was to be my turn-around point, and almost the end of my attempt. The temperature had sunk to 32F.

I went to fill the tank with gas. At that point I was about three hundred and thirty miles from home. One third of the distance covered, I was okay, other than I was freezing … really cold. It was then I discovered that I had lost my wallet. Of all the things that can go wrong, losing my wallet was not one I had planned for. I suddenly went even colder, and had a feeling in the pit of my stomach that can only be described as a mixture of dread and horror. I frantically searched every pocket, pouch, everywhere, but it was gone. I was completely crushed.

I had called the bank that day so that they wouldnít cancel my card because of multiple purchases in three States, I had about two hundred dollars in cash just in case they cancelled anyway, and to cover other unforeseen emergencies. I hadnít covered losing my wallet.

So there I was. Over three hundred miles from home, freezing cold, butt hurting, empty gas tank, and no money other than the eighteen dollars I had set aside for tolls.

I did what every other guy would have done under those circumstances. I called my wife.

We worked out that I had enough money to get gas to return to OKC. I could buy about one and a half tanks, and the two gallons I was carrying would get me most of the way. Jodie would drive to meet me and bring money to get the bike home. The attempt at the one thousand miles was dead. She had said I had enough to get me to my planned turn-around in Tucumcari, NM, and she could wire money to Western Union, enough for me to continue. I vetoed that idea. If it went wrong, I would be five hundred miles from home, with no money, and no gas, and God knows what temperature!

I spent about an hour in that warm place, drinking hot chocolate bought with my, now precious, gas money, and trying to warm up. It was time eaten from my twenty four hours, but I wasnít really counting anymore. I now just faced a long, cold ride with no purpose other than getting safely home.

Then a miracle happened.

Jodie had manned the phones. She had tracked down the number for the last gas station and called them. She asked if anyone had found a wallet, and they had. A couple of kids had found it on the forecourt, and handed it in. It was , they said, apparently intact and still had my now cancelled Debit Card, and some cash in it. But it was still over one hundred miles in the wrong direction. Hoping there was enough cash left to get me home, I plugged the address into my navigation system, and headed back. I wasnít hopeful, and I drove the first fifty miles back to a small place called Shamrock, OK, very slowly and feeling really quite depressed about the whole venture.

As I sat in the McDonalds in Shamrock I idly looked at my countdown timer on my phone. Thirteen hours to go. I just wondered if that were enough time to cover maybe six hundred miles. I still had all the receipts I needed, and I might have enough money, but I need a new route. So I did what any guy would have done, I called my wife.

I left there with my route planning in Jodieís hands, and set off in much better spirits to retrieve my wallet. That sixty or seventy miles flew by, I wasnít too kind to my elderly, but trusty motorcycle which so far had not complained even once. I was still very cold, thirty five Fahrenheit cold, so I did what I know best. I started singing. Yeah, right there inside my crash helmet. A mad Englishman, belting along I 40 East, singing at the top of his voice all the country songs that tell the world about this desolate place we call home.

I made it to Canute, having forgotten the pain in my ass for about an hour, retrieved my wallet and it still had one hundred and eighty dollars inside. All I needed now was a route.

Jodie offered me a choice of two. First choice was to take the Indian Nation Turnpike South to Hugo, OK, or simply keep going along I 44 past Joplin, MO. How far past didnít much matter. I just need enough distance. I was mindful of the verification team who later have to work out the mileage. The key is to verify the corners. That is. whatever route I take I need to prove I was at the extremities, and couldnít have taken any short-cuts that would reduce the mileage. So I chose Missouri. It was a straight haul along I 44, and no corners to worry about. All I had to do was figure out how far I needed to run. It turned out to be around ten miles short of Springfield, MO. I had plenty of time.

The only concern was that Jodieís Mom (they were tag-teaming me), had warned that the weather forecast for that area was not good. They were forecasting snow. I didnít mind too much, I was past caring, and snow would probably mean warmer!

The run back to Tulsa was uneventful. It had warmed up quite a bit, although still chilly. The promised sunshine never materialized, but it was dry, the bike ran well and in no time at all I was at the QuickTrip at 21st and Garnet, Tulsa. This is only two miles from our previous home, so I know the area well. I was no longer short of time, and I half-contemplated a quick detour to have coffee at home, before getting back out. Another bad idea that I quickly dismissed. If I went home now I would never leave. Jodie reminded me that if I had to do this all over, the seven hundred miles I now had would have to be done again. I agreed, so I headed straight off towards Missouri, and some of the worst weather I have ever ridden through. It is worth noting here that I wasnít thinking too well, and that I owe a great deal to my wife, who offered total support, and practical skills. They got me home safely. Having said that, I refused to hear what the Joplin weather radar was telling her, I didnít want to know.

I 44 East is a good road. Wide, clear and although itís a Turnpike, that at least means a valuable time-stamped receipt.

This really is a tale of two halves, as goes the old soccer cliche. The first half marked by the cold and loss of my wallet, with its attendant gloom, and the second half is a story about the weather.

As I approached the Missouri State line the road became wet. It wasnít raining, but it clearly had been. The further I went, the wetter it became. I could see the line of storms in front of me, but I had no way of knowing where they were going next. It is usual for a line running northeast to south west to be drifiting east, with the storms moving along the line to the north. I was heading east and they were in front, so for the moment I was okay. Then it started to hail!

Hail in this area, at this time of the year is not to be trifled with. As I watched it bouncing off the road, the bike, my crash helmet, I was aware that it means one of two things. Either a winter storm is coming, and this is just hail, or there might be a tornado right behind it. I scanned the skies. It was still broad daylight, and I could see no wall clouds or funnels, so I figured this was the preferable, winter storm variety hail. Well that just means that itís cold, and Iíve done cold, and cold is not going to stop me a mere two hundred and fifty miles from home. There was little in the way of rain, but the spray thrown up by the trucks was annoying. I was sore every where by now. My bum hurt something fierce, and I was shifting positions every thirty seconds to relieve it. The cold had gone through me, and whenever I tried to move my feet, pain shot right across my back. Strangely, I was not feeling tired, or sleepy. This was a trick being played upon me by my body. It was keeping me alert so that I could appreciate all the pain. I didnít know whether to be pissed or pleased.

What is it about eighteen wheelers? Anyone who rides will know that passing a large truck is not pleasant. The buffeting is disconcerting at best. It makes the front of the bike wobble. Thatís not dangerous, you just relax and let the bike manage it, which it does. But when you pass more than one truck, say on an incline, it is even worse¶. And those things always seem to hunt in packs. I had chosen Sunday to be riding in the vain hope that there would be fewer trucks on the Interstates. Fat chance, they were everywhere. I was wishing I was in France where heavy vehicles are banned from the roads on Sundays, and the rest of us get to use them in relative peace.

Te next stop was Joplin, MO. The stops were getting longer. I needed to thaw out a bit before the final out-leg to Springfield. It was getting harder because every mile was still taking me away from home. Under the old plan I would have been getting closer to home each minute. I know this isnít real. One thousand miles is the same distance however you do it, but it didnít feel like that. Reluctantly, I saddle up and head east.

Itís quit hailing now because itís raining. The road is busy and I worked out I need a minimum of sixty miles before I can turn around. Itís hard. Every mile I am looking at the trip meter and despite my speed, they take forever to mount up. At fifty I am looking to turn around. Just five more miles. At fifty five I want to go home. Just five more miles. I would hate to do all this and not go far enough over the thousand to get a Certificate, so I press on. At sixty miles I spot a great gas station, so I stopped. That should be enough and I fill up, get the receipt and spent a little while warming up, with more hot chocolate.

Then I called my wife again. ďIím at the turn-around and Iím coming homeĒ. That was pretty much all that was said. I still had about one hundred and fifty miles or so, the weather was dreadful, but I didnít care. I was going home. Still the Yamaha was behaving perfectly, it was I who was in danger of letting the bike down, but I wasnít short of time so I was okay about it all.

I now had a mere one hundred and sixty miles to go. I had a full tank of gas, and I could have covered that with the two spare gallons. On the other hand, a stop was a break, and I could afford the time. I stowed the phone in the tankbag because it was expensive and itís not waterproof. The Garmin is. As a result, for the next leg it meant that Lattitude wasnít giving position updates, which worried Jodie a bit. I ran all the way back to Miami, OK in the dry! It just happens that way.

I called home from Miami, and I was shivering. Jodie could tell. I assured her I was fine. In fact, the only time in the whole trip that I had felt at all weary, was the first part of the run back to collect my wallet. That was a low point. From then on I had remained alert and cheerful. It stayed dry to the end of the Will Rogers Turnpike, so I stopped for a few minutes and dragged the phone back out. Safely mounted it would send out its signal again.

At this point it would be reasonable to assume that the worst was over. I certainly felt that way. I was fifty miles from home, and had three hours to get there. The fifty miles would take me twenty two miles over the one thousand I needed. I was cruising. I could take it slow and easy. No point in rushing now and making some disastrous mistake. Although I knew I was tired, I didnít feel it, but slowing down a bit seemed sensible.

Well I did slow down. I slowed not just because I was being careful, I slowed because the weather Gods had one last trick to play on me, and it was going to get much worse than anything thus far. It rained. It rained pretty heavily. In a car, you flick on the wipers, crank up the heater a bit, yell at the kids to be quiet and just get on with it. On a motorcycle, when you have already covered nine hundred and seventy miles today, itís not so easy.

You try to keep your visor clear, you keep away from trucks because every time one passes you, or you them, your visibility goes from poor to zero, and you are left trusting that the road is where you think it is, and that the other drivers can see you. To that end I have a couple of modifications to the bike. The standard headlight has been replaced with a HID unit (more of that in a bit), and the rear has a whole array of high intensity led lights. They make me very visible, providing that folk are paying attention.

As I approached Claremore, OK, I was watching the total trip recorder on the GPS. It was 998 miles and counting. I watched it through 999, then every tenth of a mile until that magic number arrived ONE THOUSAND miles. I had done it. I was done, made it, verification be damned. I had ridden one thousand miles and I knew it. I didnít say much, or doing anything more that let out a satisfied ďYesĒ, with a grin so wide it nearly dislodged my crash helmet. There was still real work to be done. I was twenty two miles from home and it was about to get even worse. Still , we, the Yamaha and me, we had done it.

I left the Interstate for the last few miles and ran into problems. The road, despite the great headlight, went invisible. It was black, unmarked and wet, and I had about six miles of it. I couldnít see a thing. My glasses had steamed up and the light canít illuminate a black, unmarked road when itís wet. I sat at the side of the road, called Jodie and explained, then wondered how I was going to get the last few miles to get a till receipt.

In the end I just did it. With almost no visibility I managed to dry my glasses and keep most of the rain from them while I limped the few miles to a well-lit highway. I even missed the access road and had to turn around to get on. The last eight miles were easy, and I obtained a receipt at the gas station I left from twenty two and a half hours earlier. I didnít need gas, and I didnít want a full tank when I got home. I think the cashier thought I was some kind of wild man, because I just told him I wanted to buy something, anything that would give me a till receipt. I bought two Bic lighters, and left happy.

As I rolled the bike into our garage, with Jodie waiting, it was all too much. There were tears. Would I do it again? Probably, but not for a few days!

Lessons learned:

The guys on the Iron Butt Forums know what they are talking about. Listen to them very carefully.

Lights! You need very good ones. The HID single lamp conversion I have is terrific when itís clear and dry. When itís wet you need more.

Keeping accurate logs is vital. It sounds like a no-brainer but believe me, when you are seven hundred miles into your ride, record keeping is not straight forward. You start to forget little things so get a routine, and stick to it.

You will slow down, and the stops get a bit longer as the miles build. Allow for that.

Donít do what I did, and go when itís cold. It was dumb. Even if it was doable at the forecast temperature, it doesnít take much to make it a nightmare. I had great clothing. When I removed the outer layers at home, everything underneath, except my feet, was bone dry. Get good clothes.

The rider is more vulnerable than the bike. A well sorted bike will run while ever it has gas, the rider is the weak point. So go rested, eat and drink regularly.

Split your cash. Keep some inside your inner clothing, and if you then lose your wallet, or get your card cancelled, itís not the end of the day.

Have back-up. This success would have been a failure had I not had Jodie at home helping me when I needed help.

GPS and the G2 phone were worth their weight in gold. Donít leave home without them.

A good seat is not a luxury, it will make or break you. You can ride with a little discomfort, but the pain produced by a poor seat will finish you off. There is a reason good seats cost money, spend it.

Finally enjoy yourself. This is one of the few things you will do in your life that you will never forget. Try to make the memories happy ones.